My father taught me well the power of the word. When a great man speaks, a god listens. Had Odysseus known he had Olympus’ ear? Perhaps. The gods delight in tricks; his cleverness must have pleased them. Two boons, they granted him that day: the fame he sought, and me.

The first time a game was played for my hand, my father set the terms. My father, an oath-maker and a betting-man, taught me well the power of the word.

It is so, ARACHNITSA, he said, stringing his great bow – for he was also a shooting-man, though his arrows found their mark only half as well as his winging words. It is so, he said, as his knuckle-knotted knee bore his weight down onto the arc, his brown arms sweat-straining to bend wood to meet string. The bow is made to bend, ARACHNITSA, never break. Just so, a man who bends his words will never break an oath.

Men of my father’s age fear a broken oath. They do not fear the wailing horns of war, the bristle of a thousand enemy spears, at which they charge head-on like blinkered bulls. But words are sacred. They are the silver thread that spans between each of us, snagging, netting; invisible as the silk spun by the ‘little spider’ that was my father’s epithet for me. To defile a sacred thing was to call godswrath upon you, and that, they knew well, was a fate worse than death.

My father was speaking in figures: he did not deign my hands for bow strings. It was by the loom that I came to take his meaning. The thread had to be twisted, doubled, if it were to have any strength to it. And just as practice made my fingers deft upon the shuttle, so did I learn to unpick a man’s pretty, dissembling words. Silence is a woman’s province. Though our veils made our vision dim, they schooled our ears to sharpness. By my eighteenth year, I could discern a charlatan by his honeyed-tongue – which is why, when I first heard Odysseus speak, I knew him for what he was.

My father arranged my marriage with an unwilling heart. No great beauty, I; though all the women of our house paled to dull jewels beside Helen’s shining star. Neither had I my sister’s girlish charm, nor Clytemnestra’s pride. And yet, out of all his daughters and nieces, my father loved me best. Had my mother not insisted, he would have kept me by his side: a dutiful daughter to tend him into his twilight years. But my mother was as tenacious as she was jealous. Seeing my cousins married to the brother-kings of Mycenae had wrinkled her pride. I was every bit as royal as Tyndarius’ daughters, she claimed. I too, should marry a fine prince. And as no prince, fine or otherwise, had yet lept forth to woo me, she begged my father to intervene.

Prudent Icarius made no promises. He said he would try.

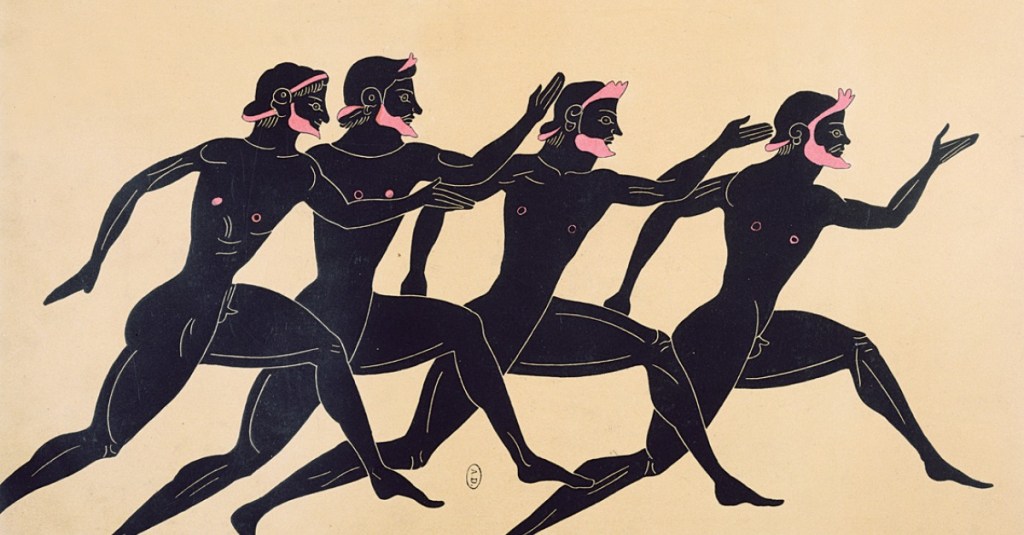

The proclamation travelled far, and fast; scattered across the Aegean on the heels of a winged sandal. From the shadowed woods of Crete to stony Semothrace, my father’s challenge rang. Beat Icarius of Sparta in a foot-race, and claim his eldest daughter as your prize.

An impossible task. All knew that my father was the fastest man alive. But that was the lure, you see: an impossible deed could make a man a legend. In this age, fame was a currency weightier than gold.

The suitors came. They came on high-necked horses, whose coats rippled and shone like expensive silk. They came in fretted carriages, pulled by sweating servants. It was a long and weary march through Laconia’s hills and vales; our closest harbour was Gythio, a full day’s ride away. So they arrived in streams and trickles, and I spent long hours at the window, assessing each new contender that passed through the gate.

I found the men of Hellas as varied as the birds in our valley. A fact I did not appreciate until all were gathered in the courtyard before me. Rheumy-eyed warriors, older than my father, stood shoulder with lissom, beardless youths. Here were kings, and princes, and second sons – and I faced them as one faces a feast for which she has no appetite: with knots in my belly and bile in my throat.

“A good turn-out,” remarked my mother, bracelets jingling on her wrist as she fanned herself listlessly. I was squashed between her and my sister, and the flesh of her arm pressed moistly against mine.

“Ay,” my uncle concurred. Tyndarius sat before us on the dais, an aging king sagging under the weight of all his gold. As my father’s elder brother, diplomacy dictated that he oversee the proceedings; it was evident he wished to be elsewhere. He suppressed a yawn. “Not as many as vied for Helen’s hand, of course. But a fair number, nonetheless.”

My mother sniffed.

It was a blazing day. Heat rose in ribbons from the sun-scorched flags. The suitors were removing their fine garments of turquoise and indigo, discarding them to their attendants’ waiting arms. Stripped of their royal trappings, nothing distinguished them from normal men. Their close-gathered bodies, already starting to sweat, filled the air with a sour musk. My brothers smelt this way after training with their practice swords. I hadn’t known it was a scent all men shared.

Another thing I learned that day: that men’s bodies also come in all manner of colours and shapes. My sister, who was younger and had not shared a nursery with boys, giggled at their nakedness. So much skin, a glut of it; sagging and taut, ropey and plump. Some had greased themselves, the better to display their gleaming muscles as they flexed and limbered. Like peacocks after a mate, I thought, though this display was certainly not meant for me. They meant to intimidate their rivals.

They were excited. The air hummed with it; an eagerness that was almost a battle-frenzy. We raised our men-children to be warriors, but it had been a long time since war ravaged these lands. A contest was the next best thing. My father descended from the dais, and this sea of brazen flesh swarmed to meet him. Only one hung back from the crowd. He reposed against a pillar in the colonnade’s shade, propped up by his canted hip. He had arrived with the suitors, but no-one attended him, and he held himself apart from that mob. Quiet: observing. I could not see his face, though something in his posture suggested an amused smile.

The races began. I think my father said some words, or my uncle, perhaps. I do not recall them; the knot in my belly was a two-headed serpent, writhing itself to a tangle. Needles pricked my palms and the soles of my feet.

Soon, a pattern developed. Before each bout, the next challenger would approach the dais. He would name himself, his father, and the land from which he hailed. He would offer me a compliment, at which I would politely smile, then he would assert that he would be the champion that won my hand. And then my father would beat him.

Time had not stolen Icarius’ legendary speed. The self-confidence upon which he’d wagered me proved well-founded, and as my nerves dissipated, boredom replaced them. We couldn’t see the runners. A man was positioned above the gate to watch the diminishing figures and narrate what he observed. The afternoon waned long and dull. I caught my uncle’s head lolling on his shoulders. My sister fidgeted, while my mother drank her misery.

The last suitor came the closest to victory. By that time, the sun had passed his wide arc through the spotless sky. The shadows of the pillars stretched over the courtyard, where the competitors huddled in disconsolate clumps. The air had cooled, and our sweat with it, so that I shivered where the fabric of my dress ghosted my prickled skin. Then, the watcher on the gate stood suddenly erect.

“Icarius of Sparta is slow on the turn!” he declared in disbelief. “Prothous, son of Tenthedron, from tree-clothed Pelion – he advances! He closes the distance…he keeps it – he is at fleet-footed Icarius’ heels!”

My heart pulsed ice through my blood. Mouth dry, I tried to recall the runner’s face. I could not conjure him. My mother stirred beside me, sitting up in her chair.

“Prothous, son of Tenthedron…which one is he?”

“Rangy-looking fellow,” my uncle supplied.

“Is he wealthy?” The wine had loosened her tongue. As she drained her cup, it darted out to chase an errant drop that dribbled, like blood, from her lip.

My uncle shrugged. “Reasonably so. His father is chief among the Magnetes, and Prothous will inherit that position.”

Pelion…I searched my knowledge of the place. A mountainous region, once home to ravaging Centaurs. Peleus had married the nymph Thetis there – would I wed this Prothous on its shady banks? It would be cold on the mountain. Cold, and very far from here. As if in anticipation of those biting mountain winds, a shudder ran through me.

“They approach the finish line!” The watcher announced. “Prothous, son of Tenthedron presses Icarius of Sparta…but he does not overtake!”

The sound of galloping feet, quiet, then growing louder – a figure burst into the courtyard, and a heartbeat later, a second man followed him. Their forms were vague against the brilliant sunset that flared through the open gate. I squinted, desperate to identify the man who crossed the threshold first. The second runner collapsed onto his rump, winded.

My father was left standing.

“Icarius of Sparta has the victory!”

Relief so sharp it stung me – I could have wept. My father beamed a satyr’s smile. Ruddy-cheeked and frenzied, like a reveller of the horned god, he cut a wild caper around the courtyard, flaunting his vigour before the defeated suitors. My mother made a small sound of distaste. My uncle groaned.

“Alas!” my father cried. “All the fine bachelors of Hellas, and not one of you worthy of my daughter’s hand!” They shot him with disdainful looks, but he heeded them not. Like misfired darts, they glanced off his shoulders and clattered to the ground at his gambolling feet. Then, in his gleeful folly, my father danced a step too far. “By Zeus, I swear it,” he declared. “Nobody can beat Icarius of Sparta, the fastest man in the world!”

Flinching, I glanced up to the darkening sky, half-expecting a bolt of lightning from the heavens. But no dreadful portent followed: no bird-omen winged overhead, and no thunder rumbled the pines. Instead, a man’s voice filled the silence.

“You claim a premature victory, Icarius King. Here is one bachelor yet to try.”

His voice was not honey. It was liquid silver: languid as firesmoke, and smooth as pooling silk. The hair raised on the back of my arms as I watched the stranger push himself up from the pillar where he leaned. I had forgotten all about him; the others hadn’t noticed him at all.

My father glanced about wildly. The smile had dropped from his face as abruptly as snow drops from a laden branch. “Who speaks?” he demanded. “Come forth!”

The crowd parted, and forth he came. There were some snickers. Compared to his fellows, the man was rather short. Sturdy, but compact: built more for wrestling than racing.

“Nobody can beat Icarius of Sparta, you said? By Zeus, you swore it?” Again, I did not see him smirk – his expression was sober. His smile was in his voice. And it was a toothy, lip-curling smile; one a fox might wear as it came upon a hen-house.

My father’s look bespoke ruffled feathers.

“So I did,” he said, uncertainly.

In one succinct motion, the stranger disrobed. The hair of his body was as dark and curling as the locks on his head. As he dropped his chiton, I caught the flash of a long, white scar along his inner thigh.

“Well, then: thus I name myself.” The man sketched a shallow bow. “I am Nobody. Icarius of Sparta, will you race me?”

Did I imagine my uncle’s amused chuckle? I could have sworn he cocked his head in recognition. But if he knew this man, he gave no verbal sign. He simply waited, as we all did, to hear my father’s reply.

What else could my father do?

“I will race you,” he said. And thus, he was ensnared in the trap his oath had woven.

My father lost the race. I had known it would be so, the second they set off from the mark. My certainty was not a coiling snake, but a still and heavy thing; a stone in my belly. The stranger had been cunning, to let the other men do his work. Perhaps there had been a god’s hand in it, too: perhaps only divine intervention could have weighted Icarius’ feet.

He should not have sworn on Zeus.

No one cheered for the victor. Even he seemed almost remorseful as he jogged past the finish line. There was no love lost for my father that day, but it was hard not to pity him as he trudged through the courtyard, his proud head hanging low.

My uncle had no such reservations. He alone stood and applauded the stranger. “At last, a champion,” he said, positively gleeful, as he beckoned the man forth. I felt sure, now, that he knew him; that he took great pleasure in playing along with the pantomime. “Come, sir Nobody,” he said, gamely. “Tell us your real name.”

The stranger took a moment to compose himself. He picked up his discarded robes and draped them over his shoulders before he approached the dais.

“I am Odysseus,” he said, head inclined in the barest bow, that his eyes were not cast down. He would not be dazzled by our Spartan gold. “My father is Laertes, who lives on Ithaca.”

A rippling murmur passed through the crowd.

“Laertes,” my uncle repeated. “That is a name I have not heard in many years, and the sound of it is most welcome. Could your father be that Laertes, who was Jason’s shipmate on the Argo?”

“Ay, the same.”

“Yes, a very welcome sound indeed; and a welcome sight, to see you standing before me, Laertides. I had not heard your father’s name in so long, I wasn’t sure he’d lived to bear a son.”

A subtle jibe. It was aimed more at my father: a final, fatal blow to Icarius’ wounded self-esteem. See what happens, little brother, my uncle was saying, see what good comes from your clever games? You end up with a nameless-nobody for a son in law.

It was aimed at my father, but I caught the pop of muscle in Odysseus’ jaw. His father and his fame are the two things that men value most, being above all else prideful creatures. And here had my uncle slighted both.

“It is not surprising, Lord, that you have heard little of us. You, who is King of all Sparta. Our islands are small, and news, perhaps, does not fly fast over the Ionian Sea. But now that you have heard the name Odysseus, you shall not forget it.”

My father taught me well the power of the word. When a great man speaks, a god listens. Had Odysseus known he had Olympus’ ear? Perhaps. The gods delight in tricks; his cleverness must have pleased them. Two boons, they granted him that day: the fame he sought, and me. It took many years for my husband to learn that recognition is a double-edged blade. Lucky for him, that on that day, the right god was listening.

The next time he spoke those words, they undid us both.

creative writing greek mythology historical fiction homer penelope (the odyssey) short story short story series the odyssey woman of warp and weft